Research and Innovations

Ground-breaking portable technology, which extends the time donor livers can remain viable outside the body, could help alleviate an acute shortage of Canadian organ donors which has resulted in one-quarter to one-third of patients dying on waitlists for liver transplantation.

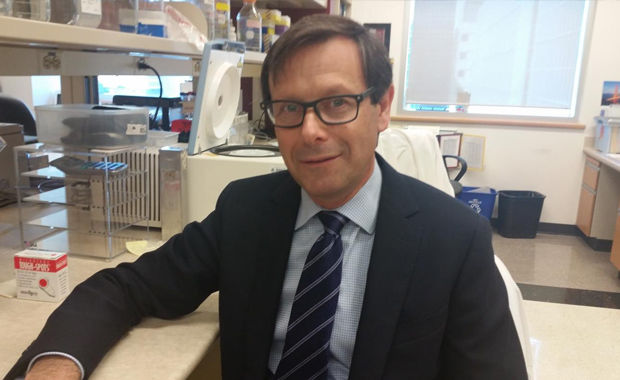

Warm liver transplantation “represents a really dramatic shift in our thinking and in our ability to preserve organs in a better way,” says Dr. James Shapiro, Canada Research Chair in Transplantation Surgery and Regenerative Medicine at the University Of Alberta. This March, Dr. Shapiro carried out the first warm liver transplant in North America. Three other transplants using the new liver preservation device, all of them successful, have been performed so far.

For more than 40 years, donated livers have been stored in “the same type of cooler that you might buy from Canadian Tire,” points out Dr. Shapiro. “You’ve got this complicated technology and yet we’re shipping the organs around the country in a simple icebox.”

“I could see in the future that probably all organ systems will at least partially use warm preservation.”

With the new device, once the organ is removed from the donor, tubes are connected to the main blood vessels and the liver is put in the machine, where it’s kept warm, pumped with blood, and has the nutrients it needs to thrive. “It basically provides everything the liver would need outside the body to keep it alive,” says Dr. Shapiro.

Similar ex vivo devices have also been used in lung transplants, and a version for heart transplants is currently in development. “I could see in the future that probably all organ systems will at least partially use warm preservation,” says Dr. Markus Selzner, a transplantation surgeon with Toronto General Hospital’s Multi Organ Transplant Program. Along with Dr. Shapiro, he is leading a Canadian National Transplant Research Program multicentre trial in clinical liver transplantation using the new machine.

Surgeons will be able to transplant with confidence

The new technology will enable doctors to know how well a donated liver is functioning, by looking, for instance, at whether it is continuing to produce bile. Dr. Selzner believes doctors will be better able to assess the quality of organs, meaning they will be able to “transplant with confidence.” He estimates that about one-third of organ donations are discarded, often based on little information – “really we have to make a guess” about their quality.

Dr. Selzner, who sees the potential in the technology for actually improving organs, notes that research is also being done to enhance organ preservation fluids so that they help make the organ more resistant to the stress of transplantation.

Live liver donation

Donation from live donors is another way to increase the organ pool. Dr. Selzner recently led a study that suggested that liver transplants from live donors appear to work just as well as traditional transplants for patients with acute liver failure.

“There is an ever-rising gap between our available supply and the potential demand – and that demand is increasing,” says Dr. Shapiro, who attributes the rise in demand for livers in part to the rise in obesity, which can lead to liver disease.

For his part, Dr. Selzner wishes families would talk about organ donation before a health crisis occurs. “I think many more people probably want to be a donor than you think,” he says. “It’s such a terrible moment to ask a family for a donation when someone has just died.”

(This article first appeared on Personal Health News)